Nov. 6, 2022, column from the Amarillo Globe-News:

'Belfast,' 'Derry Girls' illustrate times of Troubles in Northern Ireland

By Mike Haynes

Since the

Reformation, most of the countries of Europe have been split at one time or

another between Catholic and Protestant. Martin Luther kicked off the divide

when he posted his 95 complaints about the Roman Catholic Church in 1517 in

Germany, and people for centuries after were jailed, exiled, burned or beheaded

– by both sides – for not having the correct beliefs.

One of the

modern periods of conflict that continued the discord was the Troubles, about

30 years of violence from the 1960s to 1998 that brought fear and uncertainty

to the people of Northern Ireland.

The Troubles weren’t entirely a Catholic-Protestant thing; the causes of the strife also included longstanding political and cultural tensions between the Irish and the English.

But to grasp

the effect of the Troubles on the men, women, boys and girls of Northern

Ireland, two recent bits of pop culture have enlightened me and my usual movie

and TV partner, my wife, Kathy.

The birth of

friction between Northern Ireland and England followed the invasion of England

by the Normans and William the Conqueror in 1066. About a century later, the

British found their way to Northern Ireland with settlers establishing

themselves there and making that corner of the Emerald Isle much more English

than the rest of Ireland.

Fast-forward

to the 1960s, and the native Irish there, mostly Catholic, were pushing back

against those who had become Protestant and against the British soldiers who

patrolled the streets to keep order. The British ruled Northern Ireland, but some

supporters of independence became violent. Bombings were done by both sides in

the largest city, Belfast, and in Londonderry, or Derry.

In 1972,

British soldiers shot at Catholic protesters, killing 14, in an incident that

became known as Bloody Sunday. In 1979, Queen Elizabeth II’s cousin, Lord

Mountbatten, was killed along with three others in a bombing of his small boat.

The Troubles

continued with about 3,600 people killed until 1998, when politicians finally

brokered the Good Friday Agreement that ended hostilities.

That’s a

too-brief historical outline of the Troubles. But to understand the culture of

the time, the attitudes of ordinary people and how the uneasiness seeped into

daily life, literature can assist us. And sometimes movies rise to the level of

great literature.

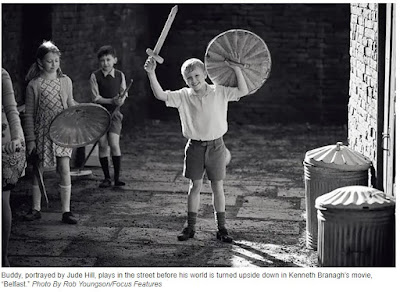

Kenneth Branagh’s 2021 film, “Belfast,” fits that category. The young boy Buddy, based on Branagh’s 1960s childhood in the city, sees violence in his own neighborhood, his dad being intimidated by young activists, barricades in the streets and a store being ransacked. His mother and dad, tied to Belfast by a long family history, talk about leaving for a safer life in England. They attempt a normal life, taking the whole family, grandparents included, to see the 1968 movie, “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.”

Buddy becomes

infatuated with Catherine, a pretty girl at school, but he doesn’t know what to

think when he finds out her family is Catholic. His is Protestant. Buddy’s dad

eventually tells him that if she’s a good person, whether Catholic or some

other religion, she’s welcome in their house.

Trying to

make sense of the violence, Buddy asks, “Was that our side that done all that to

them Catholic houses in our street, Daddy?” Also trying to make sense of it,

his dad replies, “There is no our side and their side in our street. Or there

didn’t used to be, anyway.”

Kathy and I

both put “Belfast” on our lists of all-time favorite movies.

And you also

can get some perspective on Northern Ireland from a sitcom. “Derry Girls” on Netflix

has finished three seasons about four schoolgirls and a guy who live through

the 1990s period leading up to the Good Friday Agreement. Because of some

pretty raunchy language – Irish versions of teenage cussing – we can’t

recommend it for everybody. But even in silly comedy episodes, the attitudes of

Derry kids, parents and neighbors about the Troubles come through.

The one male member of the group, James, is English, and he comes in for verbal abuse about his accent and for being, well, English. He’s loyal to his friends, though, and dresses as an angel as the girls do for Halloween – although everyone else thinks they’re swans.

British

soldiers with machine guns patrol the streets as the Derry girls take abuse

from the local shopkeeper who yells at them for complaining that the American

flag he is selling is faded and has the wrong number of stars. The sequence is

in an episode about the visit of U.S. President Bill Clinton in 1995, which

figured into the eventual end of the Troubles.

“Derry Girls”

is hilarious and also gives insight into history that most Americans know

little about.

Northern

Ireland in 2022 is experiencing political controversy about trade at the

borders that observers hope won’t inflame old wounds from the Troubles that

were thought to be healed. Working people and families certainly don’t want to

return to the days that Irish band U2 sang about in 1983’s “Bloody Sunday”:

“Broken

bottles under children’s feet, Bodies strewn across the dead-end street.”

Bono and

other U2 members hoped that the good news of the God who both Catholics and

Protestants worship would prevail forever:

“The real

battle just begun (Sunday, Bloody Sunday), To claim the victory Jesus won

(Sunday, Bloody Sunday).”